CHALK UP ANOTHER ONE FOR THE COPYCATS

As I have written previously in this blog, Judge Lourie, writing for the Federal Circuit in the Columbia v. Serius case, put a dagger in the hearts of design patentees by saying, in essence, that a copycat defendant who otherwise infringes a patented design can potentially avoid liability simply by putting its logo on its product.

Unfortunately, the good judge has set back design patentees once again in Lanard Toys Limited v. Dolgencorp LLC, Ja-Ru, Inc., and Toys “R” Us-Delaware, Inc. (2019-1781, May 14, 2020) in allowing an admitted copycat to escape liability.

I. CLAIM CONSTRUCTION

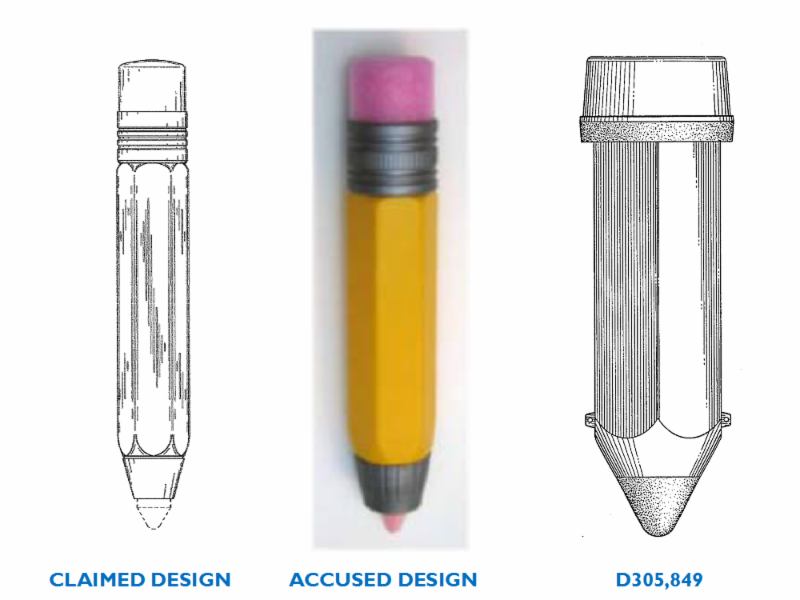

In Lanard, the claimed design (U.S. Pat. No. D671,167) is a toy chalk holder, as was the accused device, to wit:

The claim of Lanard’s ‘167 patent is what one would expect:

“The ornamental design for a chalk holder, as shown and described”.

Copying was admitted: “It is undisputed that [the defendant] used the [patentee’s design] as a reference in designing its product”. Slip op. at *3.

During claim construction, the district court considered Lanard’s argument that the recitation of a “chalk holder” in its claim was important, saying: “This construction of the claim is critical to Lanard’s patent infringement argument because it relies heavily on the chalk holder function of its design as the overriding point of similarity between the patented design and accused design that is absent from the prior art.” However, the court disagreed with Lanard’s argument:

“[T]o the extent that Lanard’s argument is that the court should consider the article of manufacture itself as an element of the design separate from its visual appearance, the court is not persuaded. Such an argument is inconsistent with the long-standing principle in design patent law that “[u]nlike an invention in a utility patent, a patented ornamental design has no use other than its visual appearance,” such that “its scope is ‘limited to what is shown in the application drawings.’”

To support the foregoing, the court basically said that the protected design is limited to what is shown in the drawings, and that the language of the claim and specification doesn’t matter.

Upon review of the district court’s claim construction, the Federal Circuit said:

“[T]he district court fleshed out and rejected Lanard’s attempt to distinguish its patent from the prior art by importing the “the chalk holder function of its design” into the construction of the claim. [W]e see no error in the district court’s approach to claim construction.” Id. at *13.

This conclusory treatment sidesteps an important issue in the case, namely whether the specific language in Lanard’s claim should be taken into account in determining infringement.

In brushing off this question, the Federal Circuit failed to consider its own precedent Curver v. Luxembourg from September, 2019. In Curver, the Court found that the title/claim of the design patent definitely mattered in determining infringement.

The patentee’s claim in Curver was: “The ornamental design for a pattern for a chair, as shown and described”, and the accused infringer used substantially the same pattern on a basket. In finding no infringement, the Court in its claim construction said that the word “chair” limited the scope of the design patent.

In the Lanard case, however, neither the district court nor the Federal Circuit gave any weight to the fact that the claimed design was for “a chalk holder”. The infringer made a chalk holder, but none of the prior art designs - none of them – was for a chalk holder.

This raises some interesting questions to ponder:

Should weight have been given to the fact that both the patentee and infringer made chalk holders, and the prior art reviewed by the district court - although rife with pencils and pencil-shaped objects – was devoid of chalk holders?

Should the prior art relevant to validity and infringement be limited to chalk holders, or extend to any object that looks similar to Lanard’s design?

If the prior art included a hand-held pastry dispenser that looked exactly like Lanard’s chalk holder, would that invalidate the patent?

Would a designer of toy chalk holders look to No. 2 pencils, beverage containers and/or pastry dispensers for inspiration in designing a new chalk holder?

What is the nature and scope of prior art that an ordinary observer should be aware of when considering whether a patented and accused design are substantially the same?

Would Lanard have a cause of action for infringement against someone who made a beverage dispenser that looked exactly like Lanard’s chalk holder?

II. INFRINGEMENT

The district court considered 8 pieces of presumed prior art, illustrations of which were included on p. 33 of its opinion. The court relied heavily on the No. 2 pencil as prior art (it was mentioned 41 times in its opinion), even though Lanard’s design was clearly shorter and stubbier than a No. 2 pencil.

Lanard’s Claimed Design

In its review of the district court’s summary finding of no infringement, the Federal Circuit quoted the lower court with approval:

“The district court thus recognized that “the overall appearance of Lanard’s design is distinct from this prior art only in the precise proportions of its various elements in relation to each other, the size and ornamentation of the ferrule, and the particular size and shape of the conical tapered end.” “

Differences in proportion, size, shape & ornamentation between the patented design and the prior art are important considerations in determining infringement – especially if the accused design shares similar differences with the prior art, as is arguably the case here. In other words, given the differences between the claimed design and the prior art, and given the fact that similar differences with the prior art are also found in the accused design, does this not support the position that the patented and accused designs may be closer to each other than either is to the prior art, which would make out a decent case for infringement?

Under these circumstances, could not a reasonable jury find infringement? Was summary judgment, reserved for cases where no reasonable jury could find infringement, appropriate here?

Interestingly, regarding the summary judgment issue, Judge Lourie dissented (without opinion) in the very recent Spigen v. Ultraproof case where the Court reversed a lower court’s grant of summary judgment of obviousness, saying that a reasonable jury could indeed find the claimed design non-obvious. Does this suggest a trend to affirm summary judgments that take the teeth out of design patents? Hopefully not.

Before the district court, Lanard relied on similar proportions of the patented and accused designs to establish infringement. The district court rejected this, saying that the relative size and thickness of the designs as compared to No. 2 pencils is a "functional modification necessary to accomplish the chalk holder function of the devices". This seems tantamount to the court saying that yes, they look different, but only because you designed a chalk holder and not a pencil.

Let’s delve deeper into the actual facts of this case, something the Federal Circuit apparently declined to do.

The district court said that "the overall proportions of the patented design are similar to the [prior art] Giant Pencil as they are to the accused design". However, upon comparing the proportions of the designs, the Giant Pencil (shown below) has an aspect ratio (length to diameter) close to 10, while that of the claimed design is around 7, and that of the accused design is close to 5.

Another prior art reference of record, the Insulating Container of U.S. Pat. No. D305,849, has an aspect ratio of about 5, making its proportions more similar to the claimed design and accused design than the Giant Pencil. A comparison of the claimed design, the accused design, and seemingly the closest prior art (the '849 patent) is instructive:

One can easily appreciate that the accused design is closer in appearance to the claimed design than either is to the closest prior art, i.e., the '849 patent. This makes a finding of infringement more likely than not, despite the minor differences between the patented and accused designs. Once again, one must ask whether a reasonable jury could find infringement; if so, summary judgment of non-infringement should have been denied.

It is interesting to note that despite numerous general references to “the prior art”, the Federal Circuit’s opinion is devoid of any illustrations or factual discussion of specific prior art, which seems at odds with its Rule 56 obligation (“In the Eleventh Circuit, a grant of summary judgment is reviewed de novo, ‘construing the facts and all reasonable inferences from the facts in favor of the nonmoving party’” (citations omitted), Slip op. at 4). In other words, if the foregoing facts about the prior art, and reasonable inferences drawn therefrom, are all viewed in favor of Lanard, summary judgment against it would seem inappropriate.

III. WAIT, THERE’S MORE!

The capper in the Court’s opinion came when it said:

“We ultimately conclude that Lanard’s position is untenable because it seeks to exclude any chalk holder in the shape of a pencil and thus extend the scope of the D167 patent far beyond the statutorily protected “new, original and ornamental design.” 35 U.S.C. § 171.”

Nowhere did Lanard seek to exclude any chalk holder in the shape of a pencil. It is an absurd position. Lanard only sought to exclude a chalk holder in the shape of a pencil that was substantially the same in overall appearance as its patented design.

Another gaffe worthy of mention is the Court’s treatment of functionality. It resurrected the discredited Richardson v. Stanley Works logic when it cited the Amini v. Anthony case for the proposition that during claim construction a district court must “factor out the functional aspects of various design elements”. This very Court has put this misguided statement to bed in the Ethicon v. Covidien and Sport Dimension v. Coleman cases that essentially found that every utilitarian feature – every one – has an associated appearance, and it is that appearance that is taken into account in determining infringement. Nothing is to be “factored out”. This goes for utilitarian features and “old” features. For example, if a design patent for some reason claims old features, i.e., features that are in the prior art, the scope of the claim will include the appearance of those features. The appearance of claimed utilitarian features are similarly not ignored. If the patentee wants to disclaim the appearance of old or utilitarian features, they should put such features into broken lines, as any design patent practitioner knows.

Sometimes it is interesting to think about what might happen if the accused design were prior art...

Musing #1: Could the claimed chalk holder have been found obvious in view of the prior art of record? In order to be held obvious, a single reference – called the “primary reference” - must be found that is “basically the same” in appearance as the claimed design. Are any of the cited prior art references basically the same as the claimed design? Under the prevailing legal standard, probably not. Would the accused design qualify as a primary reference if it were prior art? Probably.

Why is this relevant? Because the standard for infringement is whether the two designs are “substantially the same” which is virtually indistinguishable from the standard for a primary reference - “basically the same”. So, if the accused design constitutes a valid primary reference against the claimed design if it were prior art, then it also infringes the claimed design. This logic is buttressed by the requirement that obviousness is judged through the eyes of a designer skilled in the art, while infringement is judged through the eyes of an ordinary observer. The latter’s visual acuity is presumably lower than the former’s. So if a person with a greater sense of observation, i.e., a designer, finds a reference to be basically the same as the claimed design, then a person with a lesser degree of observation, i.e., an ordinary observer, could easily come to the conclusion that such designs are substantially the same.

Musing #2: Would a USPTO examiner find that the accused design – if it were prior art – anticipates the claimed design under section 102? Probably. In so doing, the examiner would apply the “ordinary observer” test which, under International Seaway*, is now the test for anticipation as well as infringement. Thus, if the accused design anticipates the claimed design, it must also infringe it.

*As I have pointed out on many occasions, including my recent paper, the International Seaway decision is deeply flawed. However unfortunate, it is still the law.