A RAY OF HOPE: CHIEF JUDGE MOORE’S DISSENT IN RANGE OF MOTION v. ARMAID CAN RIGHT THE SHIP IN DESIGN PATENT LAW

After a long wait, the Federal Circuit handed down its decision in Range of Motion Products, LLC (“RoM”) v. Armaid Company Inc. (No. 2023-2427, February 2, 2026). My blog of last week discussed the case, where I over optimistically predicted that RoM would prevail.

But the Federal Circuit, in a split decision, affirmed the district court’s findings on claim construction and non-infringement. Chief Judge Moore, in dissent, made some surprising revelations and conclusions, discussed in more detail below.

The Court majority adopted much of the lower court’s logic, such as: “We agree with the district court’s conclusion that the shape of the arms is functional.” I have pointed out the illogic of such a statement so many times that I must sound like a broken record. It is obvious that even if the arms perform a function, i.e., are utilitarian, does not mean that they are legally functional. This issue was put to bed long ago in the 1988 case of Avia v. LA Gear:

[A] distinction exists between the functionality of an article or features thereof and the functionality of the particular design of such article or features thereof that perform a function. Were that not true, it would not be possible to obtain a design patent on a utilitarian article of manufacture, or to obtain both design and utility patents on the same article.

This distinction was lost by the majority.

The Court repeatedly relied on discredited case law, including Berry Sterling, Richardson, and Lanard Toys. I will dispense with each of these.

Berry Sterling’s five “factors” for determining functionality were dicta and came out of thin air; there was no authority cited to support them. And as noted in last week’s post, the factors are relevant to trade dress functionality, not design patent functionality.

Richardson was cited to buttress the majority’s argument that requires the factfinder “to factor out the functional aspects of the design” when applying the ordinary observer test. It is not possible, physically or mentally, to “factor out” any aspects of a design if those aspects are claimed. Again, all claimed features of a design – whether ornamental, “functional” (i.e., utilitarian), new or old – must be taken into account in determining infringement – and it is not an element-by-element inquiry, it’s the overall appearance that matters.

Courts struggled with Richardson’s “factor out” test, birthed by the unfortunate statement in Egyptian Goddess that in claim construction a court could distinguish “between those features of the claimed design that are ornamental and those that are purely functional”. I had thought, like many of my brethren, that this issue had been put to rest in Ethicon and Sport Dimension. Apparently not.

I believe that courts’ fixation on “factoring” out functional features stems from a fear that design patents can somehow be used to improperly monopolize the function of a claimed design. Of course, this is rubbish. Even if a design claimed a feature that is “purely functional” (whatever that means), a design patent claiming such a feature in combination with other features does not monopolize its function. It only monopolizes the overall claimed design that might incorporate such a utilitarian feature. A competitor who wants to use such a “functional” feature can do so, and has the universe of alternate designs to choose from. What it cannot do is copy a design that’s overall substantially the same as the one claimed.

In Lanard the district court found that the title of the patent – Chalk Holder – was “functional” and did not play a part in claim construction or infringement – despite the fact that “chalk holder” was what was claimed! The district court in Lanard stated: “The construction of the claim is critical to Lanard’s patent infringement argument because it relies heavily on the chalk holder function of its design… “ (emphasis added). The Federal Circuit affirmed that finding, paying no attention to its precedent of Curver Luxembourg in which the Court found that the title/claim of the design patent was important in determining infringement. Also, Lanard has been rendered irrelevant as precedent by the subsequently decided Surgisil case and should not have been given any weight.

And, sadly, the majority relied on the “plainly dissimilar” test, discredited forcefully in Judge Moore’s dissent.

Finally, the Court majority minimized the three-way test, a test that the Egyptian court had repeatedly stated was the best way to provide a frame of reference to determine whether two designs were substantially the same. The majority affirmed the district court’s 3-way analysis that it erroneously said first required an “accounting for functional aspects”.

It is difficult to demonstrate the importance of Judge Moore’s brilliant dissent without quoting it substantially, which I do below. She forcefully addressed two main issues: in adjudicating design patent infringement, the use of the “sufficiently distinct/plainly dissimilar” test, and whether summary judgment been properly applied by district courts.

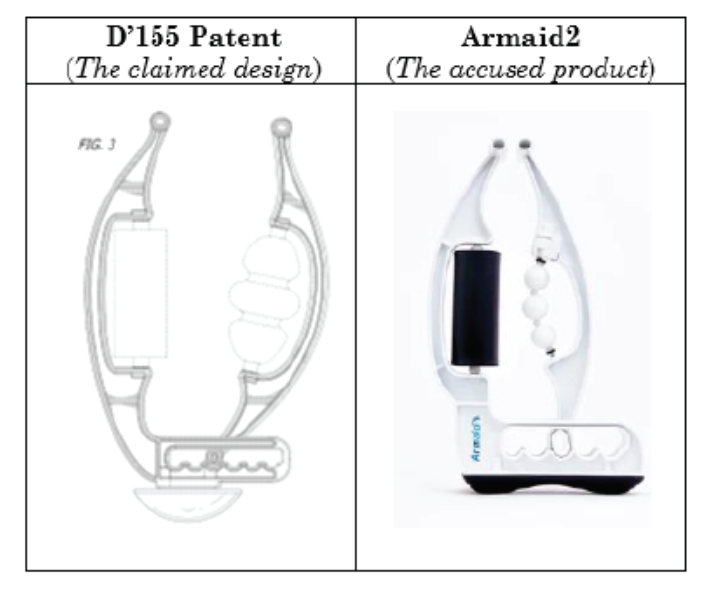

With respect to the designs at issue in RoM (shown above), Judge Moore said: “It is hard to imagine, looking at the two overall designs, that no reasonable purchaser of handheld massagers could ever find that the overall designs were substantially similar.”

Then, in an extraordinary mea culpa, she dug deeper, identifying an issue that heretofore had escaped the court’s attention:

“I believe there exists a small and easily solved problem in our design patent law that led the district court astray. A problem, which I confess, has infected several of our cases and which has been the subject of several amicus briefs to our court.

“Without realizing it, in Egyptian Goddess, we meaningfully changed the substantial similarity test. We changed the frame of reference from whether two designs are substantially similar in overall appearance to whether two designs are “sufficiently distinct” or “plainly dissimilar.”… The former causes the fact finder to focus on the similarity of the overall designs whereas the latter forces the fact finder to focus on the differences.”

She referred to “briefs that convincingly explain how this linguistic sleight of hand (substantially similar to plainly dissimilar) resulted in a significant change in the law”, citing North Star’s Petition for Rehearing En Banc and two amicus briefs filed in support, penned by Robert Oake (counsel for Egyptian Goddess), and Damon Neagle on behalf of Charles Mauro’s Institute for Design Science and Public Policy (full disclosure: I was lead counsel for North Star). The Petition and amicus briefs were cited many times by Judge Moore in her dissenting opinion. For example: “The results of a recent survey presented to this court [referencing Neagle’s amicus brief] demonstrate how impactful this paradigm shift can be. When shown designs from Supreme Court and Federal Circuit cases where infringement findings were upheld and asked whether they were plainly dissimilar, over 60% of ordinary observers polled answered in the affirmative.”

She then pointed to a larger problem: “I am even more troubled by the fact that this is not an isolated incident but appears representative of a much broader trend.

“In North Star, we affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement by holding the claimed and accused designs are “plainly dissimilar” as a matter of law.

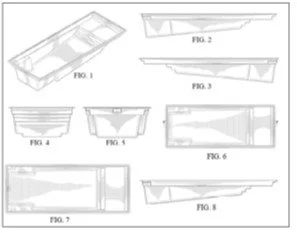

North Star’s Patented Design

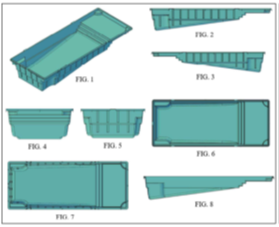

Latham’s Accused Pool

“It is hard for me to look at the patented pool design and the accused product and agree that no reasonable juror could find that their overall appearance is substantially similar.”

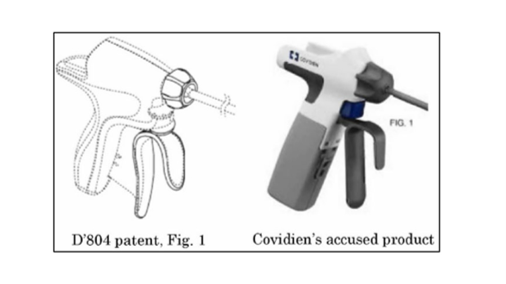

In a similar vein, she then discussed the Ethicon v. Covidien case:

“While I do not foreclose the possibility of a jury finding noninfringement on these facts, which I would affirm, I am surprised to learn that no reasonable person could find them so.

“I am troubled that such issues are being decided by district courts at summary judgment. It is not that I disagree with every one of these outcomes, which I do, but that I think there is a larger problem, of our creation. I think there is a meaningful difference between determining whether two things are substantially similar and determining whether they are plainly dissimilar/sufficiently distinct. And I cannot rule out the possibility that this paradigm shift in the law (which we created) may be responsible for these many outcomes which I find troubling.”

Then, the bombshell, which gives hope to every design patent lawyer whose client wants to assert its rights in court:

“I think we ought to correct our error in Egyptian Goddess and reaffirm that the substantially similar test, announced by the Supreme Court in Gorham, is “the sole test.”

She then discussed the district court’s analysis of the RoM case, saying:

“The entirety of the district court’s … analysis amounted to identification of minute differences in each element… Finally, after focusing exclusively on these minute differences, the court finds (again not its job on summary judgment): ‘In sum, I find that the ornamental aspects of the two designs are plainly dissimilar.’ (quoting the district court; emphasis by Judge Moore).

She then sounded a warning:

“That the district court is making fact findings cannot reasonably be denied. Nor can the fact that its entire analysis is guided by a focus on element-by-element differences. As the above demonstrates, this is not a one-off, and by this court endorsing the primacy of the sufficiently distinct/plainly dissimilar test and affirming this case decided on summary judgment: replication is certain (emphasis added). Our errant language in Egyptian Goddess has and will result in the near-complete removal of the jury from its fact-finding role in design patent infringement.”

Finally, Judge Moore proposed a striking change in the law:

“When performing the substantially similarity analysis required by Gorham, I think the court should always ‘compare the claimed and accused designs in light of the prior art’ (citing Egyptian) (emphasis by the Judge), with no special exception for plainly dissimilar designs, which has proved unworkable. … Here, the context provided by the prior art further establishes that the issue of infringement should not have been decided at summary judgment.”

In my opinion, this proposal, if eventually adopted by the court, would result in a major shift in design patent law - for the better. Far too many cases are disposed of by doing exactly what happened in the RoM and North Star cases: a court points out minor differences (there are always differences, otherwise no court case would have been brought), and concludes that the patented and accused designs are “sufficiently distinct/plainly dissimilar” on summary judgment, depriving the patent holder of a trial by a jury of ordinary observers.

In the event RoM files a Petition for Rehearing En Banc, the design patent bar should line up to file amicus briefs in support. Judge Moore has effectively provided a blueprint.

My hat is off to Chief Judge Moore.